Welcome to our series chronicling our journey from nearly failing to profitability. Make sure to read all four parts:

Part 1: A brewing storm

Part 2: Righting the ship

Part 3: Land ho!

Part 4: Charting a new course.

If you’re all caught up then subscribe to get updates from Tettra.

Whoops, we’re profitable

Me: “So I have some more news this month… Don’t worry, this time it’s unexpectedly good.”

Team: “Oh yeah? What is it?”

Me: “Surprise! We’re profitable this month, for the first time ever.”

If there was a tool that could publish a chart of an entrepreneur’s feelings, mine would probably have looked like this over the past year:

In June I had laid out a plan with my team to get to profitability, codenamed Project Gemini. It involved cutting expenses, increasing revenue and raising a bridge round from angel investors to give us more time until revenue > expenses.

Of course, I should have known that nothing would go according to plan.

“Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Revenue Forecast: Cloudy with a Chance of Money

Our goal at the start of July was to add $2,000 in net new MRR, then at least $2,500 each month after that. That meant we’d need to double revenue growth from June to July, which we planned to accomplish by changing our pricing from a per user model to a “tiered” plan model ($50/$150/$250/$500) per month based on team size. We also split the trial funnel into two paths. All teams under $50 per month would go through a self service funnel, which we called Piglets, and all larger teams would go through an inside sales funnel, which we called Warthogs.

The pricing and sales model changes helped us beat our July goal of $2,000 in net new revenue coming in at $2,217. The next month we smashed our goal of $2,500 with $3,276 net new MRR. Finally, our sales model was working! Or so we thought…

When we dove deeper into the numbers, we realized that most of the new MRR from sales came from lower-priced plans less than $150/month. According to Jason M. Lemkin from SaaStr, the cheapest you can sell a product and still use an inside sales model is $250 per month. The unit economics just don’t work any lower than that. After some digging, we also realized that those $150/month teams generally wanted to buy the product and didn’t need much convincing from a human. The self service funnel would work on them too.

When we realized this pattern we changed our prices yet again to $90/$300/$1,000 per month. The idea was to close more teams on the low end using a no-touch model. The teams that wanted a demo would get more attention from a salesperson and we’d get a higher price for giving them that extra time. Naturally, we thought giving prospects even more personal attention would make the close rate go up. It didn’t.

In fact, the opposite happened. New revenue growth slowed in September to $1,914 from $3,257 the previous month. 68% our new MRR came in from customers that didn’t do a demo.

So why was August such a good month compared to September? Well, turns out our sales team burnt the candle on both ends doing demos at all hours of the day and night to hit quota the previous months. A lot of our prospects are international which required near 24 hour coverage for demos. Not sleeping isn’t healthy, and when that behavior became unsustainable, our inside sales model became unsustainable too.

The Forgotten Half of the Profitability Equation

The second half of the profitability equation that no one really talks about when trying to grow a business is expenses. Cutting burn by 50% is basically the same as increasing revenue by 50%. Most startup founders don’t consider expenses this way. They figure, “let’s focus on growth and not worry too much about expenses right now. We can always raise more money”. We were not one of those companies.

Humans are the most expensive cost for a software startup. At Tettra, salaries accounted for 78% of our monthly burn. Our team was 6 people: two founders, three engineers, and a salesperson. Our original plan was to keep the entire team intact but pretty quickly we realized that we had to divert from the plan.

Sometimes what a company needs and what an employee wants just don’t align. One of our teammates clearly wasn’t happy with the new path forward and what we needed from him. He wanted to grow the engineering team and learn new skills. But we needed him to stay focused and keep working on the straightforward features our customers wanted. It became pretty clear that the relationship wasn’t going to work out in the long term, and we ultimately decided to part ways in July.

As a quick aside, letting someone go is always a challenge and is never fun. How you handle it is extremely important for company culture. We made sure to be as transparent as possible with the remaining members of the team on why the change was made. It’s also important to treat people well on their way out. That means being quick with the process and being generous by offering severance if you can, which we decided to do. You might might think that’s crazy to offer severance given we were bleeding cash, but it seemed like the right thing to do. How you deal with departures will be noticed by all remaining team members. Treat people fairly and humanely, and it will send an important message that you care about your people. They’ll be more likely to stick with you during hard times because they know you’ll treat them well in the long term.

Around the same time, both myself and my co-founder took pay cuts. This wasn’t ideal, but luckily the HubSpot IPO treated us both well, and we could afford to sell some of our stock to sustain us personally for awhile.

A month later, one of our other employees proactively suggested taking a pay cut. This person offered because we were transparent about our financial situation, and it was clear that this was an additional way to help the company, beyond just doing great work. We took them this person up on the kind offer and offered more equity in exchange for the salary decrease.

As you can probably imagine, during all of this my stress levels were pretty high and my mood pretty low. The team rallying to make sure Tettra stayed alive came just at the right moment and gave me a much needed boost in morale.

Not So Fun-draising

The final piece of our survival plan was to raise a bridge round to get us to profitability. I started fundraising in July. As a first objective, I reached out to our existing investors to see if they’d be willing to make follow on investments. All of our investors were supportive and not upset that the ship was on fire and about to sink. Luckily, we send out monthly investor updates, so they all had an idea generally of what was going on. But most couldn’t justify a follow on investment given the circumstances, and the few that agreed would do it on one caveat.

They wanted us to raise $500K, which was $250K more than the amount we thought we needed to reach profitability. They all thought that our plan was too tight and that there wasn’t enough slack in it to account for unforeseen issues. Doing a follow-on investment in Tettra, only to have us go out of business because of unforeseen circumstances, would have been a bitter pill to swallow.

Our existing investors committed $50K all together by the end of July and I agreed to go out raise an additional $450K more from new investors. Unfortunately, this proved to be way harder than I hoped. After another 4 months pounding the pavement in Boston and a week long trip to San Francisco at the very end of October, I resigned myself to the fact that raising the additional money wasn’t going to happen by the time we ran out of money. We had $35K in the bank and would be dead by year end.

The Captains Go Down with the Ship

Immediately after I got back from SF I bluntly laid out the direness of the situation to my co-founder, Nelson Joyce 🐟, over tacos. (It’s always easier to swallow bad news when you’re eating tacos.)

We’d definitely fail if we kept trying to fundraise because realistically we weren’t going to close the round. Given no extra money, if we continued with our current burn rate, we’d be out of money by the end of next month. There was no way we could increase our revenue fast enough to get to profitability in that time, and we already cut all the obvious expenses. It was time for immediate changes and some shitty conversations.

The first of those conversations happened right there. We’d both need to drop our already small salaries down to nothing. We both agreed we could handle it for awhile, but we’d need to talk to our partners about it and couldn’t handle it indefinitely.

Another truth we had to face was that our inside sales model clearly wasn’t working. Our customers wanted to just try the product and buy it without having to talk to a human. Using outbound spam to brute force our prospect pipeline was just something we didn’t want to do either because it’d damage our long term brand.

So the next decision was to shutter our sales team. In fact, we realized that by trying to sell through an inside sales model and raising our prices to support the cost of having sales people acquire customers, we had priced out a lot of teams that would have happily bought the product at a lower price point. We immediately lowered our prices to $60/$180/$360 and moved to a touchless sale.

Third, we had to enact forced pay cuts for six months with our remaining two team members in exchange for more equity. This was my last resort but we had to do it to cut cost even more.

Cutting the team and salaries wasn’t enough. We needed another $30K to get to profitability. Thankfully, two of our investors also really came through for us. Jim ONeill and Jessica Meher both made follow-on investments without needing us to raise a higher minimum amount. All they asked was that we worked our hardest not to fail and to not give up on the company. I’ll forever be thankful for that life raft (Thanks, Jim and Jess! 🙌)

Even with all these changes and the additional money, we still didn’t have enough cash to get to profitability. After already telling my fiancée I wouldn’t have a salary, I had to have another hard conversation with her: I needed to invest $10,000, (basically all my savings,) into Tettra to keep it afloat. That meant we’d need to defer our wedding planning. Like always, she supported me without hesitation. I’m very lucky.

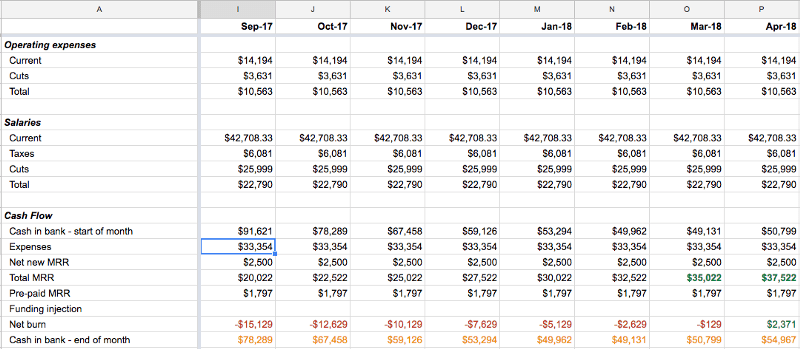

Throughout this entire process I kept a spreadsheet of projections on how fast we’d get to profitability. After making all these changes, we predicted we’d be profitable by April 2018. As long as we didn’t mess up, we could get to the point of owning our own destiny.

☝🏾 Projections Template: Sign up to get access to this spreadsheet

Whoops, We’re Profitable!

Fast forward two months to January 2018. We kick off every month with a retrospective of the previous month and some planning around what we’re going to do next. It’s a time for us to come together as a group, compare our progress against our goals, discuss what didn’t go well, talk about what did, and align on what we’re doing next to achieve our goals. We had one goal: get to profitability.

After months of delivering bad news in this meeting, I finally had something good to share: We were profitable — three months early!

Projections are usually wrong, but luckily this time they were wrong in our favor. A combination of faster-than-expected revenue growth from lowering our prices and moving to a touchless sale, along with lower-than-expected expenses, made up for the difference. Mission accomplished! 🚀

The Deathclock Stops

Startups pressure can either crush you or forge diamonds. Maintaining one’s own equanimity is a CEO’s number one skill. Over the previous months I got pretty good at that. My mood chart went from a constant state of ups-and-downs to an even keel:

This time though, it was hard not to feel excited, nay I say even optimistic. When the deathclock stopped ticking away, a switch flipped switched in my head. We were sustainable. We built a real business. We had unlimited time to grow. For the first time in a long time, my mind was free to think about how big Tettra could grow instead of constantly worrying about it exploding. Where should we go?

Curious where we’re heading next?

Then sail on to the fourth and final part of this series — Charting a New Course.